Jakarta, Indonesia Sentinel — Indonesia, the world’s largest nickel reserve holder, has drawn international attention for its bold economic policies aimed at leveraging its natural resources. However, a recent article in The Economist titled “Just because Indonesia has nickel doesn’t mean it should make EVs” criticizes the country’s electric vehicle (EV) ambitions. The critique underscores how Indonesia’s policies, while innovative in some respects, fall short compared to competitors like Vietnam and Thailand.

Nickel Policies: Success in Refinement, Uncertainty in EVs

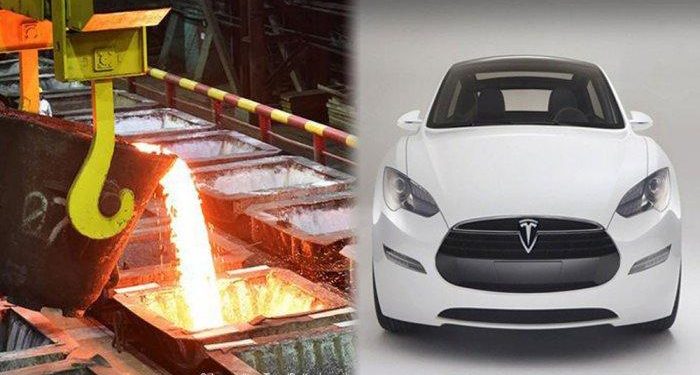

In 2014, Indonesia took a significant step by banning the export of unprocessed nickel ore. The move forced companies to establish domestic refining operations, driving investment and job creation in the nickel-processing industry. Despite skepticism at the time—fears of export revenue loss and its impact on the rupiah—the policy proved successful, culminating in a full export ban in 2020.

However, applying a similar approach to the EV industry appears more complex. Under the new government led by President Prabowo Subianto, Indonesia aims to expand its nickel-based industrial base into a full EV supply chain, from battery manufacturing to car assembly. According to The Economist, this vision is ambitious but fraught with challenges that could undermine its feasibility.

The Challenges of Competing in the EV Market

While nickel is essential for EV batteries, The Economist argues that it represents only a fraction of the overall cost of an electric vehicle. Building an EV supply chain demands much more than abundant raw materials—it requires advanced infrastructure, skilled labor, and a robust local market, areas where Indonesia currently lags behind its regional competitors.

Vietnam and Thailand, for instance, offer better logistics capabilities, higher levels of local expertise, and more business-friendly ecosystems. These advantages make them more attractive to foreign automakers seeking efficient production hubs in Southeast Asia.

Moreover, Indonesia’s reliance on nickel-based batteries could be another drawback. Many EV manufacturers and consumers are shifting toward lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP) batteries, which are cheaper and better suited for mass-market EVs. The focus on nickel-centric batteries might alienate potential investors and consumers, particularly in the domestic market.

The Cost of Ambition

The Economist also highlights the significant fiscal burden associated with realizing Indonesia’s EV ambitions. Developing an EV ecosystem from scratch demands substantial investment in infrastructure, education, and technology. While Indonesia’s fiscal health remains stable, such an undertaking could strain government finances, especially if the long-term benefits fail to outweigh the initial costs.

Additionally, foreign automakers, who are expected to transfer expertise and train local talent, might opt to bring in their own skilled workers due to Indonesia’s limited pool of qualified personnel. This reliance on foreign expertise could dilute the anticipated economic benefits, such as job creation and knowledge transfer.

President Prabowo Tightens Indonesia Fiscal Belt with $20 Billion Efficiency Plan

A Vision Worth Revisiting

Despite these concerns, Indonesia’s commitment to leveraging its nickel reserves and developing a robust EV industry is commendable. The country’s previous success in nickel processing demonstrates its potential for bold economic strategies. However, as The Economist suggests, Indonesia must address critical gaps in infrastructure, workforce readiness, and market demand to compete effectively in the global EV market.

By recalibrating its policies and fostering an environment conducive to innovation and collaboration, Indonesia could position itself as a competitive player in the EV supply chain. For now, however, its vision remains more aspirational than achievable.

(Becky)